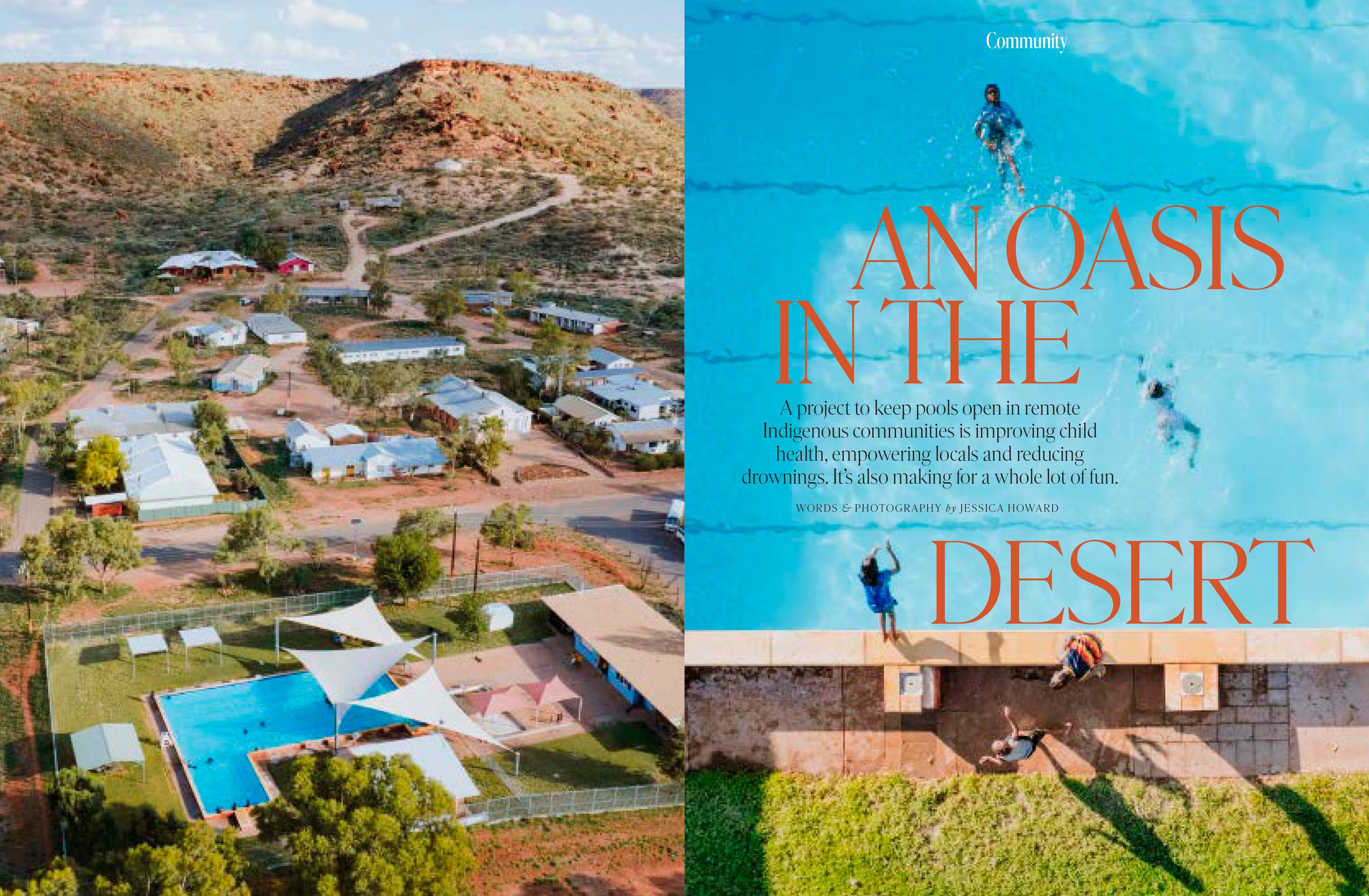

A project to keep pools open in remote Indigenous communities is improving child health and reducing drownings. It’s also empowering locals in new ways.

It’s Saturday afternoon on the brink of summer in one of Australia’s hottest places and a crowd is forming outside Santa Teresa’s community pool. A four-wheel-drive purges more passengers than it has seats and children appear from back streets - some on foot, others balancing on slow-moving pushbikes.

“Make a line,” lifeguard Patricia Oliver orders in Eastern Arrernte, the language spoken in this Indigenous community 85 kilometres south east of Alice Springs in the Northern Territory. “The kids, they know the time,” she says. “They come running and wait. This is our beach.”

There’s free entry for everyone, but under 10s are turned away unless they have an adult with them - a firm rule so lifeguards don’t become baby-sitters. On a busy afternoon like this, Patricia has enough to deal with. “I talk [Arrernte] language to them when they argue or fight,” she says, “and tell them to get out for 10 minutes. If they keep fighting - come back next day.”